The blacksmith trade was once an essential part of everyday life in Scotland. Although the occupation still exists today, it is far less common than it once was. Traditionally, there was at least one blacksmith in almost every hamlet, village and town.

As part of my series on old occupations, this blog article looks at the blacksmith trade and where to find them in archival records.

Do you have a blacksmith in your family tree?

What was a blacksmith?

A blacksmith worked with iron and steel, creating and repairing a wide range of tools and equipment.

The term “blacksmith” refers to the black metal (iron) and “smith,” meaning to strike or shape.

In Gaelic-speaking areas, the word for blacksmith was gobha, and the workshop was known as a smiddy. Actually, the word smiddy can still be seen on old buildings that once served as the blacksmith’s workplace.

Most people associate blacksmiths with shoeing horses, but in fact, their role was much broader. They made:

- Agricultural tools such as ploughs and spades.

- Components for carts and wagons.

- Household items such as griddles, fire irons, and pot hooks.

- Building fittings such as locks, hinges, gates, and other fittings.

Their work often crossed over with other occupations. For example, the blacksmith also provided some basic veterinary care in more rural areas.

Training a blacksmith

Typically, the blacksmith trade was passed down through generations. Young boys often started as apprentices, learning by observing and assisting a more experienced smith. In larger towns, a blacksmith might join a trade guild, but in rural Scotland, most operated independently or within families.

Learning the blacksmith trade took years of hands-on practice, and the tools themselves, anvils, hammers, tongs, and bellows, were often handed down through the family. In some parishes, records show blacksmith families working in the same smiddy for well over a century.

Where to find records about the blacksmith and his trade

For those researching the blacksmith trade in family history, a range of resources can help:

- Census Records: Census returns (1841–1921) list occupations such as blacksmith, smith journeyman, smith, or farrier, helping to confirm residence and household information.

- Old Parish Registers (OPRs): Baptism, marriage, and burial records (pre-1855) may note the father’s occupation. Look for these on ScotlandsPeople, especially in rural parishes where smiths served the wider community.

- Statutory Registers (from 1855): Birth, marriage, and death certificates often include occupational details. A death record, for instance, might list “retired blacksmith” or “master blacksmith.”

- Trade Directories: Directories such as Slater’s or Pigot’s list local tradesmen by name and occupation. These are accessible on the National Library of Scotland website or in local libraries.

- Guild and Incorporation Records: Blacksmiths in town burghs often belonged to the Hammermen Incorporation, a type of guild that supported craftsmen who worked with metal. These incorporations regulated trade standards and supported members through sickness benefits, funeral costs, and widow’s pensions. Contact the archive of interest and enquire about these records. For example,

- In Canongate (Edinburgh), blacksmiths were part of the Hammermen of the Canongate, one of the most influential craft organisations in the burgh. These records are held in the Edinburgh City Archives.

- The Perth & Kinross Archives have the Hammermen Society of Kinross records (reference MS14/90).

- Poor Relief and Kirk Session Records: These can contain valuable occupational information, especially when individuals sought assistance due to illness or widowhood. Available at the National Records of Scotland and local authority archives.

- Sasines and Land Records: If the blacksmith owned a smiddy or other property, they may appear in land transfers recorded in the Register of Sasines, available at the National Records of Scotland.

- Wills and Testaments: Wills may mention smithing tools, apprentices, or property. Digitised copies and indexes are available through ScotlandsPeople.

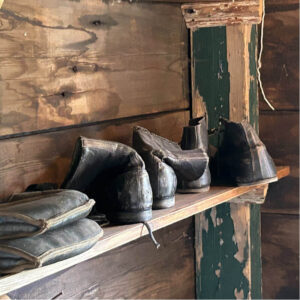

- Local Museums and Displays: Local museums such as the Abernethy Museum include displays of traditional blacksmithing tools and stories.

- Newspapers and Obituaries: The British Newspaper Archive can uncover obituaries, advertisements for smithy sales, or reports of blacksmith work, particularly in rural areas.

- Printed Sources and Published Volumes: Look for local histories and published books, such as:

- Glasgow, Past and Present, which includes reports from the Dean of Guild Court, often referencing smithy buildings and tradespeople.

- The Book of the Old Edinburgh Club, Vol. 19, which includes a detailed article on the Hammermen of the Canongate, their governance, and their role in early modern Edinburgh craft life.

The Decline of the Blacksmith Trade

The blacksmith trade began to decline by the 20th century. The rise of industrialisation brought mass-produced goods, and the invention of the tractor reduced the demand for horse-shoeing. Additionally, agricultural tools became cheaper to buy than to repair.

However, many blacksmiths adapted. Some focused on ornamental ironwork, producing gates, railings, and decorative features. Others retrained as mechanical engineers, especially during and after the Second World War.

Modern legacy of the blacksmith trade

Although working blacksmiths are rare today, the heritage of the blacksmith trade survives. Many smiddy buildings have been converted into homes, garages, or local museums.

Notable places where traditional blacksmithing is remembered include:

- Auchindrain Township, Argyll – an open-air museum with a preserved smiddy

- Highland Folk Museum, Newtonmore – where visitors can see a recreated 1930s blacksmith shop

- Local museums such as the Abernethy Museum includes a blacksmith display that showcases tools once used in the local smiddy.

In Conclusion

Blacksmiths played a vital role in everyday life across Scotland. The local smiddy was not just a place for forging tools and shoeing horses — it was often the heart of the community.

The blacksmith trade continues to spark interest among those exploring Scottish history, trades, and genealogy.

Until my next post, haste ye back.

Enjoyed this post?

Keep up-to-date with my latest posts and tips below:

We hate SPAM & promise to keep your details safe.

Image Credits: Sarah Smith

You may also like...

Is your surname Shepherd?

The surname Shepherd is one of the oldest occupational names found in Scotland. As the name suggests, it comes from looking after sheep.

My Ancestor was from Dunkeld Town

Dunkeld town, known as the Gateway to the Highlands, is located on the banks of the River Tay beside Thomas Telford’s bridge.

What is a Cordwainer?

A cordwainer is an old term for shoemaker. In Scotland, known as cordiners, they appear in many historical records and trade directories.